When I was in my mid to late 20s, I was a graduate student in the art department at Indiana University. There were a few problems with this situation, but the most important one was that I was primarily an abstract artist at one of the most figurative schools in the country. I was also shy, soft spoken, and uncomfortable talking about what I was trying to do though I had grown up in a family where artists. Sometime during my second year, the art faculty came into my studio and looked around. In my memory, I do not remember anyone saying anything. Robert Barnes, one of the graduate teachers and a painter, came up to me and said, “What is painting, is it doing or thinking?” Barnes was not tall, and he had a pugnacious, confrontational style. The way he had asked the question was as if there was a correct answer, an either/or answer. I had never even thought about it before, so I blurted out my spontaneous response, “It’s both.” Barnes turned around and without saying anything, walked out of the studio.

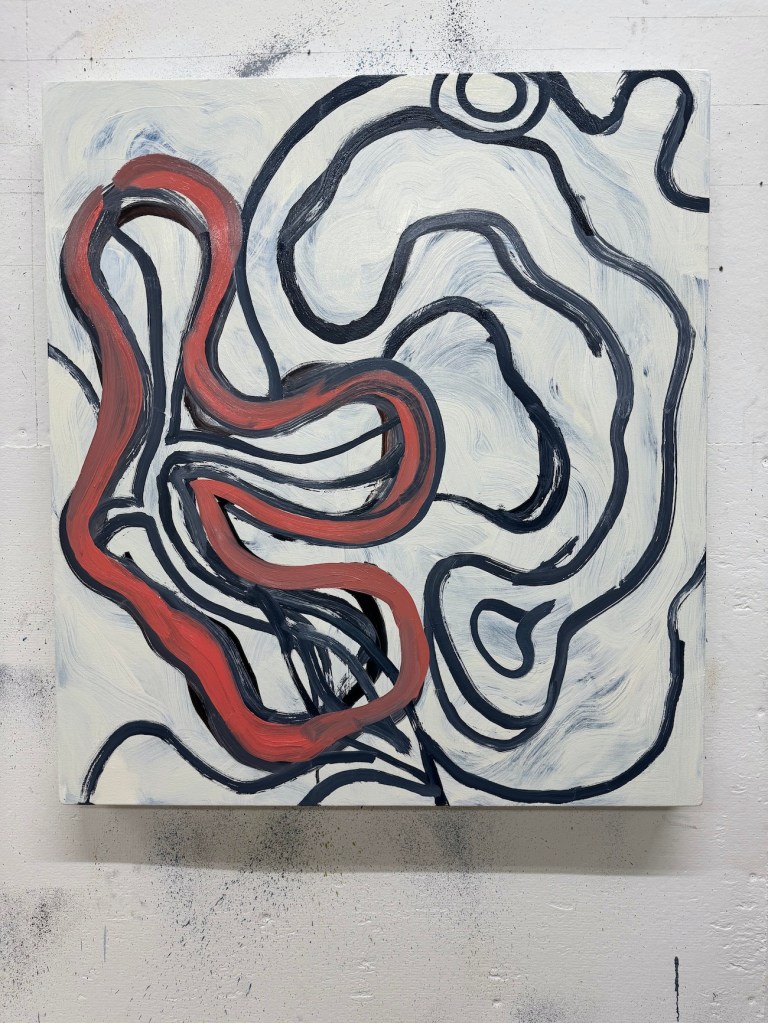

On August 25 of this year, I began this painting taking shapes and ideas from a recent painting. My idea was to keep it simple; the small size saw to that. There were just two or three shapes, and three or four, colors. To fit the shapes within the small size I rotated and placed them together, so that one shape was devouring the other. The limited colors are white, Payne’s gray, and warm and cool blue. Drawing has always been important to me, an essential means of communicating ideas. I think that part of the reason for using a limited palette is to at least maintain the fiction that what one is doing is different than drawing.

For a long time, I had been attracted to the idea of painting with just two colors, black and white. Maybe it was when I first saw one of de Kooning’s black and white paintings from the 40s, in a catalog reproduction. I didn’t see one of the originals until I saw Painting, 1948, at the Museum of Modern Art when I was a graduate student. I felt a deep emotional connection between de Kooning’s line, Ingres’s portrait drawings, and the act of drawing itself. Then there was the color, black, and its tug on my sensibilities. My father, the painter, had long made black painted silhouettes of figures, nudes in interiors, figures acting out in cityscapes with many other figures.

By limiting the painting to two shapes, keeping the size small, and narrowing the colors to basically black and white, I was reducing the quantity and kinds of choices I had in making the painting. Then I began to paint, each action such as painting the shape on the left or right or figuring out what to paint in between, was repeated. The actions of painting, I thought, did not contain the full meaning of the shapes, but they could suggest multiple meanings. To begin to make sense within the context of the painting, they were repeated.

Although some of the altered versions closely resembled the previous ones, that didn’t seem to matter as much as keeping the painting going. Why was I doing this? For one, I was delaying finishing the painting in order to leave room for accidents or unexpected happenings, such as in the seventh version. It shows the beginnings of another revision of the painting by erasing everything that had come before in the course of the painting. But instead of using that erasure as a means of revising the painting again, I kept going and painted out the rest of the painting.

The difficulty of painting is that its meaning can only be realized in the act of painting. Once I began to understand this, the process of revising a painting, the act which is about thinking, became a more desirable, if not pleasant to do. What remained were the outlines of the shapes with a little added color and hints of the turmoil underneath. I was surprised when the final state went in a new direction, the shapes becoming outlines as if I was starting over. It did not seem to matter at all what the viewer could see, the important thing was what I remembered.

1st and 2nd revision.

4th revision.

7th and 8th revisions.

Written by a human being. Titled suggested by AI. Artwork and text copyright, Peter Crow, 2025.

Leave a comment